To be honest, I strongly considered not publishing this essay. Mainly because of feared personal cost. As someone who is not yet married, or at the moment even in a relationship, I was concerned that an opinion piece like this would damage my reputation when it came to potential partners by opening me up to smears that I don’t care about the wellbeing of women. In fact, I’ve sat on this subject and have kept my feelings to myself for about a year for precisely this reason, until eventually I just came to a point where I thought the problem was getting so bad something had to be said. It wasn’t just that no one was speaking up for men, it was that no one thought men needed speaking up for.

The reception of earlier attempts, made by more accomplished writers, at cautioning the MeToo movement specifically about going too far was discouraging to say the least. Andrew Sullivan was raked over the coals for his mild-mannered concern written in New York Magazine, as was Margaret Atwood for writing similar in The Globe & Mail. The takeaway from seeing this, as a writer thinking of tackling the same subject and making the same points, was “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!” But I’ve entered anyway. And I’m perhaps masochistically curious to see what the responses will be on social media and in my inbox once I publish. I may be overestimating the level of outrage this article will generate, but I don’t think I am.

Another thing I want to stress before you begin is that this is not an article against “feminism”. I put feminism in air quotes because often times feminism is treated as a monolith, rather than a philosophical framework like every other which has divergent schools of thought and is capable of changing over time. In this piece you will encounter my usage of the phrase “modern feminism”. This is a phrase I use to describe what I perceive to be today’s dominant philosophy within the feminist movement surrounding men, while being fully aware that multiple feminisms exist simultaneously.

On a final note, this article is lengthy. It had to be. To write a shorter article would not have captured the entire scope and seriousness of this issue. Nor would writing a series of essays on each sub-issue have been ideal for maintaining the interest of readers along the way. Also, I think had I made this a series instead of one piece, it would have risked creating the impression that the subjects I discuss are separate standalone issues rather than pieces to a larger puzzle revealing—in total—the demonization of men and the suspicion of boyhood. You may not be able to read this in one sitting. That’s fine. We all work for a living, and we all have family and friends to spend time with. Read some of it, get up and do stuff, and then come back to it if you have to. I’ve even broken the article up into five sections to make it easier for readers to pick up where they left off.

Without further ado then, smile at the screen or scream at it, but regardless, enjoy.

✸

First of all, let’s begin with the obvious: Yes, boys should be raised to be compassionate as well as brave; sensitive as well as assertive; tender as well as resilient; humble as well as strong; along with a host of other smaller dualities (intellectual as well as athletic, anyone?) Most importantly though, boys should be raised to respect women. This is “most important” because 1) women are human beings of equal worth and just as deserving of dignity as men, and 2) the health of any civilization rests on men and women having good relationships and functional families. I’m sure I wasn’t the only boy in America raised to feel that if a man didn’t care to respect women or women’s boundaries—depending on the offense—you either told them off or you beat the hell out of them. That might not be the politically correct solution today, but that’s what was passed down to me by two generations of strong confident Hochdorf men and that’s what I still believe, even in our non-confrontational, bureaucratized, very soft culture. You never not intervene in a situation of harassment or assault.

Secondly, in regard to the problem I’m about to discuss—the problem of how men and boys are negatively perceived—I don’t think this problem is everywhere. I think as of right now this problem is limited to the corporate world, mainstream media, the public education system, and the professional class in major cities like New York and LA. But I don’t believe what’s about to be discussed is really an issue in small-to-midsize towns, or is an issue that plagues the average American family (most of whom make $30,000 a year and have much more pressing concerns financially in a country with extreme wealth inequality). At the moment, in short, this is largely a “non-middle America” problem. But the reason I’m writing about it is because I don’t think it will stay this way. I think the problem of how men and boys are perceived will eventually spread into wider society.

So with these two clarifications being made, I’ll cease beating around the bush: We are in a moral panic over men and boys. And the panic is quickly turning into loathing.

The panic has been going on for a few years (though some would contend it’s been happening much longer than that), but I first began to notice a shift in how men and boys were talked about in popular culture while watching the 2015 Super Bowl. In one of the ads, featuring comedian Sarah Silverman, Silverman was playing a doctor helping a mother give birth, and when the baby arrived, Silverman handed it to the mother and—cue punchline—said “Sorry, it’s a boy”. This apparent joke was praised and defended by popular online outlets including Salon, Nerve (now defunct), and Refinery 29, despite striking most men who saw it as being sexist.

Two years later, in Afghanistan, as I was surfing random websites for any news and commentary from the outside world, I came across two op-eds: one by Ijeoma Oluo—a feminist writer named one of the 50 Most Influential Women in Seattle by the Metropolitan—titled When You Can’t Throw All Men Into The Ocean, What CAN You Do?; and the other by Damon Young—a lesser-known male feminist columnist for GQ—titled How, If You’re A Man, To Deal With The Fact That You’re Probably Trash. Somewhat taken aback by both headlines, I clicked on the links and proceeded to read the following:

(Oluo)

“This [American] society is doing everything it can to create rapists, to enable rapists, and to protect rapists. This society is broken, abusive, patriarchal (and white supremacist, ableist, hetero-cisnormative) trash. Not just in little pockets. Not just in dark alleys and frat parties. It’s fucking rotten through and through and has been forabsofuckinglutelyever.”

(Young)

“We [men] are all complicit. We are all agents of patriarchy, and we’ve all benefited from it. We are all active contributors to rape culture. All of us. No one is exempt. We all have investments in and take deposits out of the same bank. And we all need to accept and reconcile ourselves with the fact that, generally speaking, we are trash.”

Despite the authors’ explosive tantrums (reminiscent of the hysterical shrieking of Maoist “struggle sessions”), both op-eds largely managed to fly under the radar in terms of responses and coverage, and I naively took that to mean they were on the far-fringes of the culture wars. In fact, my mind immediately traveled to Valerie Solanas, the famed nutball who in 1967 founded the Society for Cutting Up Men—and shot Andy Warhol with a .32 pistol—and I began to laugh that there were still individuals well into the 21st century not so far removed from her way of thinking.

But in another op-ed this past year in June—this one in the not-so-fringe Washington Post of all places—titled Why Can’t We Hate Men?, Suzanna Danuta Walters, a sociology professor at Northeastern University, dispensed the following advice:

“Men, if you really are with us and would like us to not hate you for all the millennia of woe you have produced and benefitted from, start with this: Lean out so we can actually just stand up without being beaten down. Pledge to vote for feminist women only. Don’t run for office. Don’t be in charge of anything. Step away from the power. We got this. And please know that your crocodile tears won’t be wiped away by us anymore. We have every right to hate you. You have done us wrong.”

Contrast all of this with the weak, half-hearted assurance by The Woke that “Feminism isn’t about hating men, it’s only about equality of the sexes”, and it should be no surprise that an overwhelming majority of men perceive this to be as hollow as every other marketing ploy. We just don’t believe it. The behavior doesn’t match the sales pitch.

If you had a partner who constantly criticized you day-in and day-out over every issue big and small, and if your partner had been doing this for years, never once telling you that they loved you, would you be unreasonable to conclude that your partner hated you, given their never-ending attacks and lack of regular affirmation of how much they value you? This is exactly the “relationship” men have with modern feminism. We’re constantly gaslighted with the platitudes “Feminism is not about hating men” and “Feminism is just about equality”, and yet everything said and done by the movement’s vocal proponents in recent years would suggest that modern feminism is—indeed—about man-hate and about vilifying masculinity. It’s textbook motte-and-bailey: promote radical ideas until those ideas are challenged, then act “appalled” as you retreat to the fortress of your gentle definitions.

Men Are Monsters

An assertion that has grown more and more frequent, over the past six years or so, is that “women are afraid all the time”. That men have created such a terrible social climate that no woman, anywhere, feels safe without always having her keys wedged between her knuckles. An “educational” page on the website of Marshall University’s Women’s Center claims that “Most women and girls live in fear of rape. That’s how rape functions as a powerful means by which the whole female population is held in subordinate position to the whole male population...” Yet the most stinging and dramatic invective against the un-fair sex that I’ve read comes from a user writing on the community question-and-answer site Quora, “How do you trust your world when you see what the world’s most intelligent respected men are capable of? To see them willing to use you, to accuse you of vanity when you listen to that feeling in the pit of your stomach? How do you feel about yourself when you always seem to bring out the worst in a man, a side you also wouldn’t believe existed if you weren’t facing it all alone? Without needing to attack you, it seems they teach you by a thousand small cuts how vulnerable you are.”

While this accusation of widespread male hostility toward women is a fairly broad one—too broad, I think, to fully address in one piece—one of the central talking points used to prop this idea up is the oft-repeated (and oft-reported) statistic that 1-in-4 women are sexually assaulted on college campuses.

This shocking revelation, which came in 2015, earned attention from the Obama White House, its own Reefer Madness-esque “exposé” The Hunting Ground (originally aired on CNN before being released to Netflix), and one of those Very Serious celebrity we-need-to-talk commercials with the solid backdrop (an ad cliché which can be further observed here, here, here, and even this self-aware one here). Even the New York Times—perceived by many to be a bastion of competent and thorough journalism—took the finding at face value. But while one sexual assault will always be one too many (and this is not throat-clearing, I genuinely mean this), the 1-in-4 study is highly misleading.

Prepared on behalf of the Association of American Universities (AAU), the survey attempted to be the largest and most comprehensive of collegiate women’s “campus climate” experiences, spanning 27 universities and approaching approximately 800,000 female students. Only 19% of the women approached responded, however, even with anonymity guaranteed and incentives offered. Those 19% were then asked a series of vaguely-worded questions about sensual and sexual situations without being told they were being surveyed on the subject of the prevalence of sexual assault on campuses. These vague questions ranged from whether the respondents had ever been kissed without verbal permission, to whether respondents had ever been “sexually touched” without verbal permission, to whether they had engaged in sex initiated by another party after consumption of alcohol. If respondents answered “yes” to any of the above, their answers would all be lumped into the category of “sexual assault”, regardless of if they themselves would have classified their experiences as such. I can hear the objection now of course: “Well they are victims of sexual assault, even if that’s not how they think of it!” But do women not have the right—and indeed, the agency—to determine for themselves whether or not they are victims? Wouldn’t anything else be condescending, infantilizing, and paternalistic?

Again, one sexual assault is always one too many, and giving law enforcement more tools and funds to investigate sexual crimes (including processing rape kit backlogs) is of dire importance. Yet when one looks to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ definition of sexual assault—“attacks or attempted attacks generally involving unwanted sexual contact between victim and offender, but also including verbal threats”—the number is not 1-in-4, it’s 1-in-52. In essence, an “epidemic of sexual assault” on college campuses has only been created by expanding the definition of the term which formerly had a more precise and restrictive meaning. (Partial blame belongs to the deceptively benign injunction that consent must always be “enthusiastic” or it doesn’t exist at all. We can’t be having any tired sex, grieving sex, angry sex, bored sex, or any other intimate mood that admits to the complexities of human emotion. No, every sexual encounter must feature partners who behave like go-go dancers on Ritalin, or else it’s definitely rape. Our inquisitors are nothing, in the end, if not simpleminded.)

This isn’t to say that piggish behavior or unwanted aggressiveness shouldn’t be shut down immediately. It absolutely should. And preferably by other male bystanders, rather than women always having to do the work themselves. But clearly there are gradations to certain actions that separate criminals from assholes. Even the authors of the 1-in-4 study expressed regret later on that their methodology led to a misguided and ideologically charged crusade against men, noting that estimates of assault may have been too high—not just because they had expanded the definition of sexual assault—but also “because non-victims may have been less likely to participate” in the survey.

But the damage was done. As Charles Spurgeon (not Mark Twain) famously noted, a lie travels halfway around the world before the truth can even get its shoes on.

In addition to it being in activists’ interest to repeat and display the statistic virtually everywhere one turned, it was also in mainstream media’s interest to be complicit in the statistic’s promotion. As Brian Earp puts it in this excellent Huffington Post piece, writing “Approximately 1 in 4 of 19% of a Non-Representative Sample of Women Who Responded to a Non-Representative Survey of 27 Colleges (Out of Roughly 5,000) Reported Experiencing Sexual Assault, Where ‘Sexual Assault’ is Taken to Mean Anything from Being on the Receiving End of an Unsolicited Kiss to Forcible Penetration at Gunpoint, Regardless of the Particular Context” wouldn’t make a great headline. Nor would a shorter “Latest Campus Sexual Assault Survey Paints Complicated Picture: Report Stresses Methodological Limitations”. Panic sells. And there is no panic which burns so bright and sustains itself for so lengthy a time as moral panic. Moral panic sells papers, gets clicks, and scores ratings.

Hence, this:

The wider indictment that flows from the 1-in-4 statistic—as you likely already know unless you are a hermit—is that the United States is a “rape culture”.

While one could devote an entire essay just to this concept alone, my intent—to reiterate—is to articulate the problem of the demonization of men and the suspicion of boyhood as a whole. Thus I can only spend a short time defining the concept of “rape culture” and addressing an alleged proof of it, before moving on to the impact belief in this problem has had on our social psyche.

Defined by the online Oxford Dictionary as a sociological concept wherein “a society or environment whose prevailing social attitudes have the effect of normalizing or trivializing sexual assault and abuse”, the alleged evidence that the United States is a “rape culture” is the case of Brock Turner.

Though the attack on an unconscious young woman had happened a year prior, news of the occurrence hit public awareness in 2016, when the nation was confronted with the mugshot of the woman’s attacker: 19-year-old Brock Turner, a Stanford freshman whose ice-cold vacant stare accompanied what appeared to be a slight smirk. The mugshot had been taken within an hour of Mr. Turner dragging the woman behind a dumpster and—after penetrating her with his fingers—jamming leaves and twigs into her vagina. Seconds later, he was tackled by two men who happened upon the scene and held until police could arrest him.

Almost as appalling as the crime itself was the behavior exhibited by others during the trial phase. First, local news had initially reported on the case by emphasizing Mr. Turner’s athletic ability and potential, rather than focusing on the trauma he had inflicted on another human being. “Brock Turner, a Stanford swimmer who once dreamed of competing in the olympics…” and so on. One report even listed the assailant’s swim times at the bottom of the story detailing his crime. Then, as if that alone were not bad enough, Mr. Turner’s father told the judge that his son shouldn’t have to go to prison for “twenty minutes of action”, and the judge agreed with him, sentencing the college freshman to just six months in the county jail. Sounding about white, the entire country was rightfully stunned and enraged.

But it wasn’t long thereafter that a narrative began to form in the opinion pages of popular online publications and establishment print papers, that this wasn’t just a singular case of a predator receiving less than he deserved. Rather, People v. Turner was indicative of how little all men apparently valued women. All men—no matter how polite, no matter what their age, no matter what their core beliefs, no matter what—were socialized to be Brock Turners. This was “rape culture”. And if you didn’t believe that, then you were quickly reminded that 1-in-4 women experience sexual assault on college campuses. The narratives reinforced each other.

“Sexual violence against women is not the result of a few odd, bad elements. Sexual violence is part and parcel of masculinity…” said Rama Singh at The Conversation, “While every man may not be a sexual ‘predator’, every man has the biological potential to be so. Men will continue to be threats unless the working environment becomes gender-neutral… The solution to the problem of campus safety lies in making male students aware, individually and collectively, of the dangers of masculinity. Their social upbringing combined with their biology is a deadly mix for doing harm to others.”

“The way we raise our sons has everything to do with our daughters. We raise daughters as if they need to be protected, without even realizing that it is our sons we are protecting them from,” wrote Betsy Aimee in Mom, “We are the problem, but we are also the solution. Which is why I'm passionate about raising a feminist and empathetic son.”

I also remember these sanctimonious gems back when they went viral:

Yet while the Stanford attack was indeed perpetrated by a man, it was also stopped by men and—given the fact that men comprise a majority in most police forces—it was likely that the rapist was arrested, interrogated, and charged by men. The judge who gave Mr. Turner the light sentence was (rightfully) publicly shamed and recalled.

Our society—our culture—reviled Brock Turner.

There was a tidal wave of national outrage at his sentence.

This case, rather than being proof that the U.S. is a “rape culture”, actually proved the opposite. A real rape culture would hardly have noticed such a preposterous sentence, or if it had noticed, would not have thought it unjust. This didn’t happen. And just a reminder: this guy dragged an unconscious girl behind a dumpster and began shoving his fingers and foreign objects into her vagina. If you think this behavior is inherent in the average American male—rather than the product of a uniquely psychopathic or sociopathic criminal mind—you’ve completely lost touch with reality. An overwhelming majority of American men have about as much in common with Brock Turner as they do Dennis Rader.

But the belief that all men are potential rapists and that the U.S. is a “rape culture”—given life by the erroneous 1-in-4 statistic—has led to asymmetrical coverage of stories involving men harming women, while largely ignoring stories about women harming men or each other. As a result, the public has been led to an imbalanced perception of gendered violence. Even when stories are reported about women committing crimes, those stories are never used to diagnose any “intrinsic” or “socialized” problem with women in our society as is done with men.

When 17-year-old Michelle Carter sent over 40 text messages to her 18-year-old boyfriend Conrad Roy encouraging him to kill himself—and he did—she was only sentenced to 15 months in prison; and no one suggested that she had been conditioned by misandry or “oppressive social norms” to commit that ultimate of crimes. Instead, a psychiatrist suggested Miss Carter’s depression medication was to blame for her cruel act.

When 35-year-old Tara Lambert was busted hiring a hitman—who was really an undercover cop—to kill a couple she was jealous of, her response—and this is an exact quote—was an annoyed “Ughhh… am I really, like, being arrested?” News reports about the trial in the following months described Lambert as a “femme fatale” and as “the former aspiring model who captivated a courtroom with her eye-catching outfits”. For conspiracy to commit murder, she received seven years in prison. A sentence later reduced after appeal.

When it comes to gendered violence overall, in fact, a Harvard Medical School study conducted in 2007 on 11,000 American men and women concluded that—on average—out of all relationships, 24% have seen violence of some variety; and in half of those 24% of relationships—where domestic abuse was entirely one-sided and the partners were not equal aggressors—women were the initiators 70% of the time (a study conducted almost 20 years ago in Great Britain revealed similar findings). And yet despite this evidence showing that women are just as capable of violence and just as capable of malicious intent as men, if you look at national sentencing averages, men are subject to sentences 63% longer than sentences handed down to women for the same crimes.

However, this damaging view of men as somehow being more prone to criminality—while given a boost by recent “rape culture” and sexual assault rhetoric—actually owes much of its perpetuation to the modern feminist conception of male behavior in ancient and contemporary history. Mainly, that “men have started all the wars, all the mass shooters have been men, most homicides are committed by men” etc., and therefore there must be some problem sociologically (or a few would even say biologically) with men in general.

My rebuttal to this charge is twofold.

For one, an overwhelming majority of men never live to become generals, kings, presidents, or rulers of any kind in a position to “start a war”. When it comes to those who rise to the top of hierarchies, they normally do so because they are—more often than not—psychological anomalies who transcend the typical biological traits that drive ordinary people. There’s very strong evidence to suggest that most men (and women for that matter) who become world leaders possess sociopathic/psychopathic traits, or at the very least suffer from extreme narcissism. It’s also worth noting that sexism has indeed been humankind’s default for most of recorded history, to the point where many women throughout that history have been uneducated in regard to reading and writing; and therefore, men have written most of our ancient histories. As a result, these histories have focused on other male figures when discussing acts of evil and mischief. It isn’t, then, that men in history have been more wicked and violent than women. It’s that we simply don’t know about many of the wicked and violent women. Those women have operated in the shadows of major empires and events, and are mostly forgotten if they were ever known about at all. (Off the top of my head, I can only think of Lizzie Borden and Nero’s mom).

Two, very few men ever commit acts of horrific violence like homicides or school shootings. So much to the point that to say those who do commit homicides and school shootings, do so because they are male, is just nakedly ideological. It would be like pointing out that since the majority of teacher/student sex scandals in high schools are ones involving female teachers, there must be something innately or sociologically problematic with women in general. Absurd, right? Far more productive—in examining the causes of school shootings and homicides (and teacher/student sex scandals for that matter)—would be to look for signs of mental illness, medication side effects, abusive backgrounds, or even brain tumors, rather than lay the blame at the feet of an entire gender just because all perpetrators of one type of crime have the same genitalia in common.

But I don’t just want you to focus on the demonization of men through the narrow scope of rape and other crime (though those are two major components of the argument). Instead, it’s important to understand the overall picture today’s cultural messaging conveys of men as being fundamentally creepy, men as being untrustworthy, men as being gross… men as being monsters. And if everything I’ve mentioned so far has not persuaded you of this intensifying push to see men in such a light, take a look at an Instagram post written by feminist “influencer” Kristina Maione, which has gone viral with 37,000 likes:

This rationalized prejudice is very much an orchestrated effort, and one which—of course—has a devastating impact on how men see themselves. For even if we carefully consider every word we say to female friends and colleagues and how we say them, and even if we go to great lengths to ensure nothing we do is perceived as threatening to women in public—crossing the street whenever a female jogger is coming the opposite way, for example, or making sure our hands are visible and that we avoid eye contact when crossing a parking lot late at night—we still feel like creatures, loathed and feared. How do we process being bombarded with the message that our very being is threatening? How do we cope with being told, often subtly and indirectly, that our strength, confidence, courage, and virility—attributes which have helped humanity survive and thrive for a hundred thousand years—now make us a problem to be solved?

A symptom of this male “othering” is how any instance of undeniable discrimination against men is reframed as actually being discrimination against women.

For example, when confronted with the fact that fathers are more likely to lose their children in custody disputes, modern feminists retort that these disproportionate rulings are in fact sexist against women, because such rulings assume that women are more suited to nurturing roles. Even though—in a custody dispute—one might reasonably think the mother in the situation is wanting the kids, and is therefore happy when she gets them.

And this is done with nearly every situation where the deck is stacked against men.

Did you know that “women are the primary victims of war” because “war prevents women from accessing education and becoming financially independent”? That’s what was decided by the UN Security Council in 2017, even though it’s primarily men who are shot, stabbed, maimed, captured, and blown up in war.

Did you know that high male suicide rates aren’t due to increasing unemployment, declining wages and benefits, a diminished reputation in popular culture, or the United States having the highest prison population in the world, but instead is due to “toxic masculinity”?

And on and on it goes.

Anytime any situation arises where men get the short end of the stick, it will always—always, always—be reshaped as a women’s issue. Because if we live in a patriarchy where men are the dominant group, then they can’t really face discrimination or unfair treatment unless that discrimination or unfair treatment can somehow be tied back to patriarchy. And we wonder why men are reluctant to speak up about the problems they face.

Boys Are Experiments

The natural conclusion one would be led to, after believing men are monsters, is that boys are monsters-in-training unless there’s drastic intervention. Underpinning this conclusion are two intertwining philosophies—one old and one new—that are, frankly, just bad.

The first philosophy used to support the idea that boys can be “retrained” to overcome allegedly constructed masculine behaviors, is that human beings are blank slates. That is, all behavior is learned and everything is social construct. Human nature—in the evolutionary biological sense—does not exist, but is a fiction driven by archaic sexist patriarchal assumptions operating under the guise of “science” (a field that, the far-fringe of feminism would contend, is itself a tool of Western hegemony). No innate differences exist between boys and girls, and any percieved differences should be proven easily interchangeable. More feminine virtues like sensitivity, vulnerability, gentleness, and nurturing should be encouraged in boys, and more masculine virtues like risk-taking, assertiveness, fortitude, and firmness should be encouraged in girls.

But “difference” doesn’t automatically mean inequality, and acknowledging that gender differences exist on the genetic level does not translate to believing one gender should have dominion over the other.

As the famed linguist and psychologist Steven Pinker pointed out in his 2002 book The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial Of Human Nature (which you can find on my Recommended page):

“No one has to spin myths about the indistinguishability of the sexes to justify equality. Nor should anyone invoke sex differences to justify discriminatory policies or to hector women into doing what they don’t want to do. In any case, what we do know about the sexes does not call for any action that would penalize or constrain one sex or the other. Many psychological traits relevant to the public sphere, such as general intelligence, are the same on average for men and women, and virtually all psychological traits may be found in varying degrees among the members of each sex. No sex difference yet discovered applies to every last man compared with every last woman, so generalizations about a sex will always be untrue of many individuals. And notions like ‘proper role’ and ‘natural place’ are scientifically meaningless and give no grounds for restricting freedom.

Despite these principles, many feminists vehemently attack research on sexuality and sex differences. The politics of gender is a major reason that the application of evolution, genetics, and neuroscience to the human mind is bitterly resisted in modern intellectual life. But unlike other human divisions such as race and ethnicity, where any biological differences are minor at most and scientifically uninteresting, gender cannot possibly be ignored in the science of human beings. The sexes are as old as complex life and are a fundamental topic in evolutionary biology, genetics, and behavioral ecology. To disregard them in the case of our own species would be to make a hash of our understanding of our place in the cosmos. And of course differences between men and women affect every aspect of our lives. We all have a mother and a father, are attracted to members of the opposite sex (or notice our contrast with the people who are), and are never unaware of the sex of our siblings, children, and friends. To ignore gender would be to ignore a major part of the human condition.”

Regardless, the belief persists that boys can—and should—be socially engineered by school teachers and “woke” parents to reject masculinity, as part of an overall mission to make future generations more androgynous (again, difference is perceived as inequality). Of course, most proponents of blank slateism and social engineering would frame their project in slightly different terms. Their goal, they would tell you, is not some vast attempt to eliminate gender or multiply genders to such a number that they become meaningless by virtue of their infinitude, but is simply to rid boys of “toxic masculinity” (though frequent users of the term never seem to get around to articulating what in their view would constitute a good manhood).

“Toxic masculinity”, the second philosophy that underpins this idea that boyhood requires intervention, is a phrase you’ve come across before in this article, but which has never been described up until now. This isn’t really my fault, for it seems that no one who uses the term can agree on what the precise meaning of it is.

“Toxic masculinity is a description of manhood designating manhood as defined by violence, sex, status and aggression,” The Good Men Project says.

“Toxic masculinity refers to a limiting, one-dimensional form of gendered behavior,” Image magazine states more vaguely.

“Discussing toxic masculinity is not saying men are bad or evil, and the term is NOT an assertion that men are naturally violent,” Teaching Tolerance reassures us.

But Collier Meyerson at The Nation begs to differ, writing “It is only with the understanding that gender identification is moveable, malleable, and worth undoing that we can begin to make the boys all right” and that “The concept of masculinity was constructed to defend white supremacy and white male dominance over black men and women of all races” (this would be news to the pre-Columbian Aztec warriors).

Infighting of modern feminists aside, however, the common denominator of “toxic masculinity” that seems to be agreed upon is that boys are conditioned—mainly by their fathers, but also by “patriarchal society” at large—to dominate others who are weaker than them and to suppress their emotions from an early age. To be more specific, the implicit assumption is that because boys and men are reluctant to cry, and because boys and men sometimes act aggressively toward others, there must be some social reason for both of those things; and since these problems occur in one generation after another, it must be fathers who are to blame.

With a worldview that says everything is social construct and nothing is biological, this would be the natural conclusion that would result. The only problem is, boys’ and mens’ reluctance to cry or express vulnerability does have an evolutionary explanation: sexual selection.

Males in our distant past who showed signs of distress (i.e. crying, panic, or any anxiety in between) communicated to the females of their tribe that they were incapable of being adequate protectors and providers for their potential partners and offspring. By contrast, males who displayed a lack of fear in the face of danger signaled to the females of a tribe that they were capable of protecting and providing, and were therefore more likely to be selected for reproduction.

As Charles Darwin noted in his 1871 work The Descent Of Man:

“When the males and females of any animal have the same general habits of life, but differ in structure, colour, or ornament, such differences have been mainly caused by sexual selection; that is, individual males have had, in successive generations, some slight advantage over other males, in their weapons, means of defence, or charms, and have transmitted these advantages to their male offspring.”

Given enough time of this happening, it’s easy to see how the message became encoded in mens’ genes that to be appealing to the opposite sex, we must be “strong”. The way to display strength, our ancestral code tells us, is to have an absence of any emotion that reveals vulnerability. In our modern world—where emergency services are merely a phone call away—this approach is no longer a necessary component to sex and life, and our definition of strength has now expanded to the emotional realm. Men can cry, men can express fear, men can reveal concern. But “caveman DNA”, so to speak, still resides in us. We still have that internal signal telling us that to be open, unguarded, and even momentarily delicate is not okay.

The blame, in other words, for boys’ and mens’ reluctance to embrace sensitivity and vulnerability does not lie at the feet of our fathers or society, but at the feet of our fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’ fathers’… and the brutal chaotic environment that shaped them a hundred thousand years ago, before society ever came to be.

And even now, as far as we’ve come, studies continue to show that women—generally speaking, as always—still are not attracted to men who cry or express other signs of sensitivity on a frequent basis. Thus, unless we are willing to contend that women too have “toxic masculinity”, perhaps we should throw out this notion that “boys are being ruined by dad and patriarchy” and instead make better attempts at understanding our evolutionary past.

This statement would, of course, be met with extreme hostility by the staff at Seafarer’s Preschool in Stockholm, Sweden, who have made it their mission “to counteract traditional gender roles and gender patterns” by experimenting with the toddlers under their care.

According to the New York Times:

“Something was wrong with the Penguins, the incoming class of toddlers at the Seafarer’s Preschool, in a wooded suburb south of Stockholm. The boys were clamorous and physical. They shouted and hit. The girls held up their arms and whimpered to be picked up. The group of 1 and 2-year-olds had, in other words, split along traditional gender lines. And at this school, that is not O.K. Their teachers cleared the room of cars and dolls. They put the boys in charge of the play kitchen. They made the girls practice shouting ‘No!’…

It is normal, in many Swedish preschools, for teachers to avoid referring to their students’ gender; instead of ‘boys and girls’, they say ‘friends’ or call children by name. Play is organized to prevent children from sorting themselves by gender. A gender-neutral pronoun, ‘hen’, was introduced in 2012 and was swiftly absorbed into mainstream Swedish culture, something that, linguists say, has never happened in another country. Exactly how this teaching method affects children is still unclear…

A columnist and mathematician named Tanja Bergkvist, one of the few figures who routinely attacks what she calls ‘Sweden’s gender madness’, says many Swedes are uncomfortable with the practice but are afraid to criticize it in public. ‘They don’t want to be regarded as against equality,’ she said, ‘Nobody wants to be against equality’…

When boys in the group for 3-year-olds refused to paint, or dance, and the group threatened to split along gender lines, [the on-hand gender specialist] was brought in to unpack the problem, tinkering with the activities until she coaxed the boys back to equal participation…

One of the group’s teachers, Izabell Sandberg, 26, noticed a shift in a 2-year-old girl whose parents dropped her off wearing tights and pale-pink dresses. The girl focused intently on staying clean. If another child took her toys, she would whimper. ‘She accepted everything,’ Ms. Sandberg said, ‘And I thought this was very girlie. It was like she was apologizing for taking up space.’ Until, that is, a recent morning, when the girl had put a hat on and carefully arranged bags around herself, preparing to set off on an imaginary expedition. When a classmate tried to walk off with one of her bags, the girl held out the palm of her hand and shouted ‘No’ at such a high volume that Ms. Sandberg’s head swiveled around. It was something they had been practicing. By the time March rolled round, the girl had gotten so loud that she drowned out the boys in the class, Ms. Sandberg said. At the end of the day, she was messy. The girl’s parents were less than delighted, she said, and reported that she had become cheeky and defiant at home. But Ms. Sandberg has plenty of experience explaining the mission to parents. ‘This is what we do here, and we are not going to stop it,’ she said.”

Aside from the fact that a teacher in her twenties “explaining” to me what she “wouldn’t stop doing” with my child would rue the day she was born (because—Sweden, United States, or Timbuktu—I’m the parent, and what I say in regard to my child is what goes), notice the current of biology that lurks beneath and throughout this story, even through a neutral-to-sympathetic telling by the New York Times.

“The group of 1 and 2-year-olds had, in other words, split along traditional gender lines…”

“Play is organized to prevent children from sorting themselves by gender…”

“When boys in the group for 3-year-olds refused to paint, or dance, and the group threatened to split along gender lines… she coaxed the boys back to equal participation…”

In other words, there’s a sort of tacit admission among those who claim that gender is a social construct, that gender differences do occur on an instinctual level among small children, and can only be temporarily offset by aggressive intervention in an artificial environment. This is really important. For if gender were truly a social construct, all the Seafarer school would have to do is create the neutral “gender free” environment and then let the toddlers loose in that environment, with little-to-no staff surveillance or intervention necessary. That so much “hands on” indoctrination is needed, should tell the remaining sane Western world all we need to know about the genetic foundation of gender differences.

But the war against “toxic masculinity” doesn’t merely end with eliminating gender. It also involves punishing boys who are “too far gone”. At the Mercer Island School District in Washington in 2015, elementary school administrators banned boys from playing tag because it “violated the physical and emotional safety” of the female classmates. At Baltimore’s Park Elementary School in 2013, a 7-year-old boy was suspended because he had chewed his pop-tart into the shape of a gun, which, in a letter written by school officials, was classified as “an inappropriate gesture that disrupted the class” and warranted the boy being “immediately removed from the classroom”. Nationally, young boys ages 7-13 are three times more likely than girls the same age to be diagnosed for hyperactivity disorder because of “aggressive” playful behavior, and 20% of American boys will be on medication for ADHD by the time they reach high school.

To be clear, all of the precise psychological and physiological differences between men and women can be challenging to define or identify at times, and said differences—even when identified—only apply generally and not in every case. When one considers traditionally masculine attributes/virtues like risk-taking, assertiveness, confidence, and strength, for instance, it would be absurd to assume women do not also possess these attributes. I’m lucky enough to know many women in my personal life who have all of the above. But when it comes to the differences between male and female brains, it isn’t so much about variation as it is degree. If we think of the mind like a collection of valves, for a moment, as a helpful image, it becomes easier to grasp that while men and women have the same neurochemicals (testosterone, estrogen, etc.), the male and female brain release different amounts of those neurochemicals at different times, which in turn produces different behavior (generally). This doesn’t mean men should run all the businesses or that women belong in kitchens. But what it does mean, is that aggressive attempts at changing the fundamental nature of human beings will leave boys (and girls for that matter) confused, frustrated, repressed, disoriented, and damaged.

MeToo: From Justice To Inquisition

In 1983, the Manhattan Beach Police Department received a report from Judy Johnson, a young mother who claimed her son had been sexually molested by a teacher at McMartin preschool named Ray Buckey. Buckey was the grandson of the school’s founder Virginia McMartin, as well as the son of Peggy McMartin who—at the time—was McMartin’s administrator. In addition to the accusation of molestation, Miss Johnson accused staff at the McMartin preschool of having sex with animals in front of children and of “drilling a child under the arms”.

Police subsequently sent several hundred McMartin children to be interviewed by Children’s Institute International (CII), an abuse therapy clinic run by a woman named Kee MacFarlane, who claimed to be a psychotherapist but who held no professional licenses. The institute conducted the video interviews with the children using puppets, and confirmed soon thereafter that they had, in fact, been molested.

When the Manhattan Police Department then charged seven of the preschool’s staff, including Ray Buckey, and Virginia, Peggy, and Peggy-Ann McMartin on one hundred counts of child molestation, a national panic soon followed. Reports poured in from all over the country alleging “molestation rings” in preschools and daycares, and televangelists, news anchors, law enforcement officers, and parents of McMartin children couldn’t flood the airwaves fast enough to warn other parents about the silent epidemic. And why wouldn’t that happen? The children at CII had, after all, stated in the interviews that they had been molested… hadn’t they?

Not exactly. When the defense was allowed to review CII’s taped interviews (at that time sealed by the court), they found that none of the children had stated they had been molested or assaulted until they had been coaxed and even, at times, coerced to say so by Miss MacFarlane and her staff. What was worse, the prosecution had withheld certain key details about the case from the defense throughout most of the trial. Judy Johnson, the initial accuser, for instance, had previously been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic who—in addition to alleging child molestation and bestiality to the police—had also accused Ray Buckey and the rest of the McMartin staff of being able to levitate, and of having conducted satanic rituals which could summon demons. She would later go on to claim that there were underground tunnels beneath the preschool, where children were taken to observe animal sacrifices. When these details about the accuser came to light so late in the game, federal agents investigated the preschool grounds, and no signs of animal sacrifice or satanic ritual were found. Nor—in case you were wondering—any underground tunnels.

Three years after her initial accusation and halfway through the McMartin trial, Judy Johnson was found dead in her home. The cause of death was determined to be complications from chronic alcoholism. By 1990, all seven defendants had been cleared of all charges. But the damage was done. By the end of the trial, Ray Buckey had been jailed for five years without ever being convicted of a crime. McMartin preschool closed its doors and the family became reclusive. The national panic had fizzled out, having been built on nothing but lies, righteous indignation, and sensationalism, but what it left in its wake was a string of ruined reputations and the people of a nation unnecessarily plagued by a fear of their neighbors.

When I first heard about this incident from a New York Times Retro Report (which I suggest you watch below), I was amazed at the failure of integrity and due diligence which seemed to have happened at every level. The accuser was insane. The police department and the prosecutor moved forward regardless. The therapist (who was actually not one) had guided the interviews. And the media went full speed ahead.

But I was also intrigued by another detail that stood out about the McMartin case: how much the life of this panic depended upon a moral obligation placed on the shoulders of the public to believe. In the New York Times video, a woman giving a press conference (mother? lawyer?) shouts to the surrounding reporters and the audience they were broadcasting to, “Wake up America! This is your wakeup call! We believe the children, because once upon a time we were the children, and nobody believed us!” People marched with signs and bumper stickers reading WE KNOW THE TRUTH. WE BELIEVE THE CHILDREN!

This reaction by the parents and by the public is what I want to direct your focus to. Yes, the details of the case itself are interesting and not unimportant, but the response in particular illuminated a very disturbing feature of how human beings in large groups—certainly in the context of American history—have tended to operate in times of fear. When allegations reached their most extreme, and emotions ran high, you were a bad person if you didn’t believe.

This is typical whenever a moral panic takes hold of a population. It happened with the McMartin panic, it happened with the “satanic panic” which occurred at the same time (and which overlapped with the McMartin case), it happened with the “Red Scare” in the 1950s, it happened with the Reefer Madness panic of the 1930s, and if you wanted to go really far back, it happened in the town of Salem in the 1690s.

We have a tendency—especially as Americans, with our puritan origins and long history of religious revivals—to want to make everybody conform to righteousness when convinced that some form of depravity is “epidemic”. In the heat of a moral panic, once right-thinking is determined by a social mob, any deviation from that right-thinking is pounced-on and swiftly condemned. (That this conflicts with another deeply American impulse—free expression and dissent—so beautifully encapsulated in Patrick Henry’s exclamation “Give me liberty or give me death!”, is a subject of fascination, but is also another article for another day.)

Bearing this context in mind, we are brought, at last, to the MeToo movement.

MeToo, in the beginning, was a force for good. I really do believe that. Here was a mass movement of regular people—mostly empowered women—who were going after criminals. A big-time Hollywood producer, a famous news anchor, a political pundit on a rightwing TV channel, and an award-winning actor were all being named-and-shamed as sexual predators who for too long had evaded justice.

But it didn’t take long before the MeToo movement became less about exposing individual criminals and more about the condemnation of men as a whole, and before we knew it, panic rhetoric began fueling proclamations in media about the need to rethink sex, dating, consent, male-female interactions, everything. Literally everything. Even old romantic movies and photographs. Nothing could be left alone, nothing was sacred, because—we had been told—the “MeToo moment” was a watershed moment. A revolutionary event of which there was a definitive before and a definitive after. A moment modern feminists took as confirmation of all their gender theories and notions of a conspiring patriarchy lurking around every corner. Don’t you see? Here is the proof! Here is the proof that toxic masculinity exists! Here is the proof that American men are problematic! We’ve been saying it for years. What more do you need to be persuaded that we need radical change?

One such change the American public is instructed to adopt—especially men who want to prove themselves “one of the good ones”—is to automatically believe women when they come forward with harassment, assault, or rape accusations. We are told that women choose not to come forward with accusations much of the time because they fear they won’t be believed, and therefore, in order to encourage more women to come forward when they’ve been victimized, it is our new moral obligation to believe all accusers. And if you refuse to conform to this new moral obligation, you’re a bad person. You’re “part of the problem”.

Naturally, concern has been raised about false accusations. In a new social environment where women who accuse men are automatically believed, what would stop a woman from taking advantage of such a climate for vengeful or ambitious reasons? But in response to this very valid concern, proponents of MeToo’s shift toward the extreme have poured scorn on those who raise the point. Why The Male Fear Of False Rape Accusations Should Worry All Of Us, Afraid Of False Accusations? Try Trusting Women, and The Bad-Faith Of #HimToo are just a few examples from around the web of this rebuke, and—as mentioned in my beginning statements—writers like Andrew Sullivan and Margaret Atwood were the ones most loudly crucified for daring to raise minor objections to the excesses of a movement they supported.

When Andrew Sullivan wrote “No one is or should be defending abuse of power. It’s foul. I’m glad certain monsters have been toppled… but nuance, context, and specifics matter”, a majority of the 93 responses posted beneath his Facebook link accused him of being everything from “tone deaf” to a “rape apologist”. When Margaret Atwood suggested that MeToo was entering a “terror and virtue phase”, and that the movement was becoming so radical it was almost a “religion where anyone who doesn’t puppet [extremist] views is an apostate, a heretic, or a traitor, and moderates in the middle are annihilated”, one feminist writer shot back “If Margaret Atwood would like to stop warring amongst women, she should stop declaring war against younger less powerful women and start listening.”

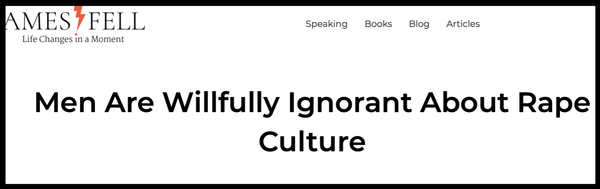

Yet the clearest dismissal of the concern over false accusations came from Emily Lindin, a columnist at Teen Vogue who tweeted:

I call this the Lord Farquaad Principle:

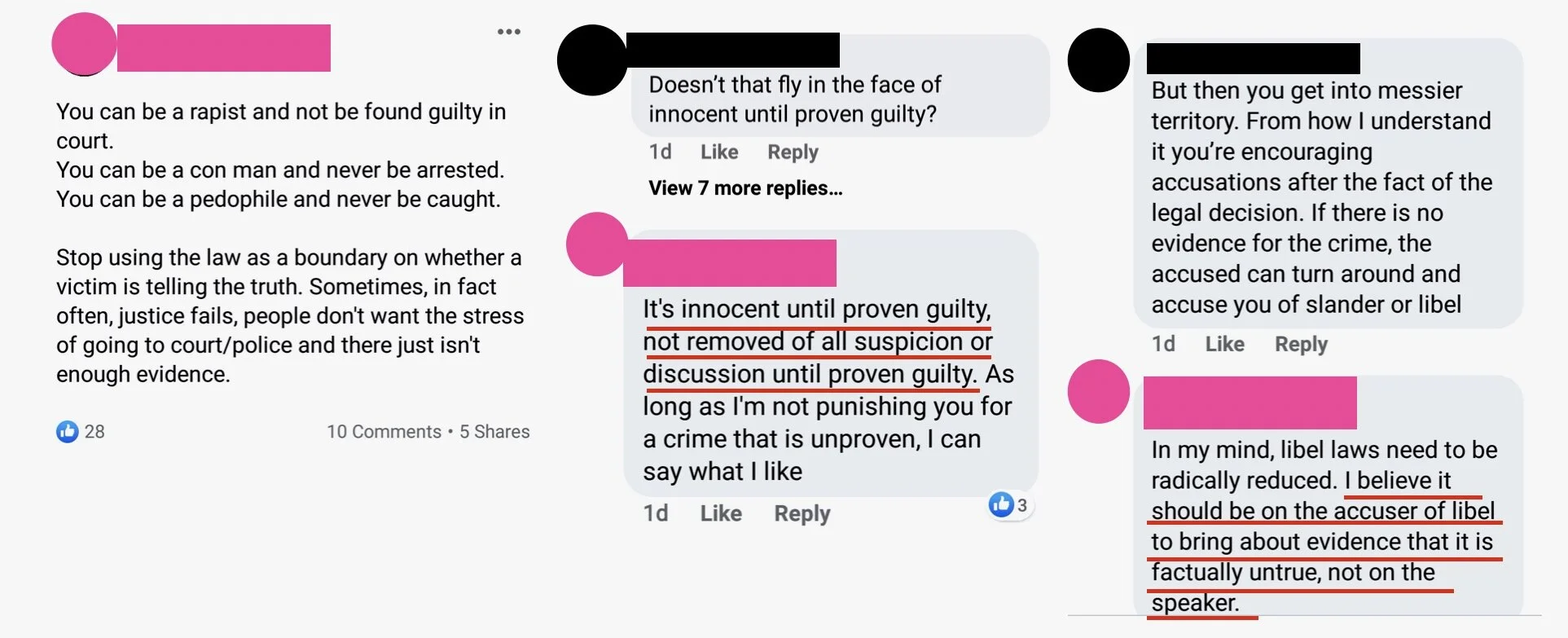

Nevertheless, the demand for evidence upon hearing an accusation is horribly misguided, we are told. If somebody came to you and said “My car has been stolen”, the argument goes, you wouldn’t require evidence in order to believe they were telling the truth. You would believe them automatically. Why, then, wouldn’t we as a society do the same whenever someone—most likely a woman—comes forward with a harassment, assault, or rape accusation? Why must we demand evidence? Isn’t our demand for evidence, evidence itself of the misogyny that runs rampant throughout our culture?

But the stolen car analogy is flawed. If someone tells you “My car has been stolen”, there is an absence in that accusation of a specific perpetrator. The car was stolen, but by who? It’s appropriate to believe someone who tells you that their car is stolen, because—until the thief is caught—no one’s life is negatively affected by the accusation. By contrast, if somebody tells you “Bob raped me”, it isn’t like believing somebody has been victimized without having to judge a particular victimizer. In order to believe the person saying “Bob raped me” you must also believe—absent any evidence—that Bob is a rapist. Imagine a culture where all a woman had to do to ruin a man’s life was accuse him of rape or sexual assault, not having to offer any shred of proof.

And yes, I’m aware that modern feminists are not pushing for a shift in the legal doctrine of presumption-of-innocence (at least not yet). I’m aware that what’s being called for is a change in social attitudes. That the courts can presume innocence all they like, but the people—the masses—should believe. But if the goal of the MeToo movement is a cultural shift where the public automatically believes accusers by default, a “not guilty” verdict in a trial won’t matter. We all know that the full scope of a person’s life (i.e. their work, their friendships, their relationships, their financial security, etc) extends far beyond their status as a mere legal entity; and therefore, to argue that men should be deemed guilty by the court of public opinion regardless of the outcome of an actual court, is to condemn them to a form of social death they can only escape by moving away, and maybe not even then.

Is it really any surprise that a movement which makes that its objective would face pushback? It shouldn’t be. And before any whinging begins about backlash, realize that male resistance to MeToo is not a backlash against holding guilty men accountable. Nor is it a backlash against “privilege” we inwardly acknowledge but outwardly won’t admit to. The backlash is against the idea that men are so disposable, and so monstrous, that what is required to keep us in line is a media and a public set against us no matter how credible our defense. If you don’t believe that this is what motivates the pushback to MeToo, read just two of the many hundreds of comments I’ve seen posted online by ordinary men on the subject.

Writes “Dan” under a Facebook article about a harassment controversy:

“All it takes is an accusation. Not a true one, not a factually-supported one, not a legal one. Those things aren’t necessary. With just one short comment on social media, a man’s entire life can be utterly destroyed. His career, marriage, friendships, reputation, status, future… all potentially gone due to one claim. In the world of MeToo and ‘believe all women’, the accusation is the punishment. Sure, sure, most of its wielders are mature enough to use it wisely. Fine. But most is not all, and there’s no way to tell the responsible ones from the irresponsible ones. For the man, every encounter, every action, every word, no matter how innocent his intentions, is another round of Russian Roulette he must play.”

“Robert” comments beneath a local news clip on YouTube:

“It seems to me that the last two generations of young ladies have been taught that their feelings are paramount and that they will never lead them astray. They’re taught that any problems in their lives are from men, the patriarchy, or whatever other nonsense. This wouldn’t be such a problem if women didn’t actually wield the majority of social power. On a whim a woman can say that you make her feel uncomfortable—not pointing to any specific action you did, just her vague feeling of discomfort—and get you investigated at your work.”

The predictable counterargument to everything these men and I are worried about, is that false accusations are so incredibly rare. I can already hear the yelling. The rage. “Only 2% of all rape allegations turn out to be false, dipshit!” Except, aside from the fact that my right to be presumed innocent shouldn’t depend on statistics (because no rights should depend on statistics), the 2% assertion isn’t true at all. The figure comes from a 1975 book Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, written by feminist activist Susan Brownmiller using rape statistics from the city of New York, not the whole country. In truth, the percentage of false rape accusations varies depending on the sources one consults. The FBI crime index puts the number of false accusations at 8%, but according to Dr. Brent Turvey, Director of the Forensic Criminology Institute, the number of false accusations could be even higher than that. In his 2017 textbook False Allegations: Investigative & Forensic Issues In Fraudulent Reports Of Crime (which I spent $100 on, so you wouldn’t have to), Turvey gathered data from eight different studies on false rape accusations in the U.S. and abroad (cited at the end), and found that false reports could range anywhere from 8% to 41% of all allegations. The reason why the percentages differ so greatly, Turvey writes, is because “Statistics are not regularly collected, nor are they broadcast outside of law enforcement. Estimates are often a closely guarded secret, generally to conceal how common the problem is.” Yet regardless of whether false accusations are at 8%, 41%, or somewhere in between, the fact of the matter is that it isn’t as low as 2%, as MeToo’s most ardent zealots would have us believe.

And lest you think I’m just trying to derail MeToo with a series of endless what-ifs, know that the damage done to the lives of innocent men is not hypothetical, nor are their stories erased by cherrypicked figures and statistics claiming they don’t matter. Just a few weeks ago, a Mexican rock musician killed himself following an anonymous accusation that he harassed a minor. In his suicide letter he insisted on his innocence. Dan Jones, who was recently profiled by 60 Minutes in Australia, spent five months in a maximum security jail because his girlfriend falsely accused him of rape. Writer and former MPR host Garrison Keillor lost his entire 50-year career for accidentally touching a woman’s back. And then there are the false report cases which came before MeToo, and after the movement’s recession from public attention: the Duke Lacrosse case, the UVA/Rolling Stone case, the Brittany Krider case, the “Mattress Girl” case, the Occidental College case. These cases…

None of this matters though to modern feminists or to the media that enables them. None of it. You have to be 100% onboard with MeToo all of the time. You must be a devout adherent. No questions, no dissent. Even as the movement creates a culture of paranoid hyper-vigilance. Believe. That is the command.

As a result, the exaltation of female rage and the canonization of women who are “angry for the cause” has become the movement’s modus operandi. Take, for example, the oft-circulated photograph of Christine Blasey Ford during the Brett Kavanaugh controversy.

While I have absolutely nothing against Mrs. Ford, and while I opposed the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh for other reasons outside the accusation made against him by her, the way the image of Mrs. Ford was presented by mainstream media speaks volumes about how gender activists want this movement overall to be received. Her eyes are closed in solemn resolve, her hand is raised in much the same way statues of deities have their hands raised to denote wisdom, and a decorative clock hangs in the background just above her head like a subdued halo. You could put the image on a stained glass window. This, of course, was not some elaborate orchestration by Mrs. Ford herself, but the circulation of that particular photograph attached to think-pieces about male entitlement and “toxic masculinity” is absolutely meant to convey that MeToo is a holy movement. A righteous war between one half of the country’s population and the other.

Hating Men Is Good Money

In November 2013, Munk Debates hosted a debate on the subject of “Gender In The 21st Century” with the motion of the debate being “Be it resolved: men are obsolete”. In favor of the motion were debaters Hanna Rosin and Maureen Dowd, and against the motion were debaters Camille Paglia and Caitlin Moran.

To a time traveler from 1998, it may have come as somewhat a surprise to see Maureen Dowd taking the anti-male position, seeing as how it was Miss Dowd who for so long caricatured Monica Lewinsky in her New York Times columns as “nutty and slutty” for falling victim to a predator president (and who, since that time, has never apologized). But nevertheless there she was, stating in a pre-debate interview: “I think that politically, biologically, sexually, chromosomally, men just basically stopped evolving. And women have been evolving at a really fast rate. The X chromosome has been really speeding ahead of the Y chromosome, which is kind of shrinking and almost going off a cliff.” When asked by the moderator/interviewer what men needed to do in this time to succeed, Dowd’s answer was blunt: “You should just do whatever we tell you.”

If such a statement—and debate topic, for that matter—had occurred in isolation, it’s conceivable that there would have been at least some outrage. But the statement, and the debate on the obsolescence of men, didn’t occur in isolation. They happened within a social context (still continuing) that for years has encouraged professional women—primarily in media, though not limited to that sphere—to bash men as creeps, idiots, slimeballs, and slobs, and to get paid doing it. In this, Dowd was hardly among the first to jump on the bandwagon, nor was she the most scathing.

On the contrary, there is a virtual army of modern feminist writers who are now given platforms in very prestigious publications for the sole purpose of cheerleading “women good, men bad”, many of whom require no introduction. Jessica Valenti, Rebecca Traister, Sady Doyle, Lindy West, Jaclyn Friedman, and Lena Dunham have built entire careers raging against men, and they’ve brought home a lot of cheddar in the process. Jessica Valenti, a Guardian columnist, pulls in at least $78,000 a year if we’re going off of what other columnists report as their salary (keep in mind she also has five published books). And I don’t think I really need to go into all the details of Lena Dunham’s wealth, who we all know is really rich, with a net worth of approximately $12 million.

If you click on my Archive page, you’ll find essays about everything from Thomas Jefferson to invectives against capitalism. You’ll find interviews with historians and dissidents, and you’ll find musings on the act of writing and death. You’ll even find a crack at poetry and some travel writing. This is because I, and writers generally, are very curious and restless people. We want the world entire. We cannot possibly consume enough information. Give us love, give us scandal, give us radicalism and dissent, give us hope, give us doom, give us politics, give us timelessness, it doesn’t matter. Even when we know that knowledge is not power, knowledge is misery (as Abbe Faria and the mythical Solomon tell us), we still chase it, it’s our drug. But many a newspaper or magazine’s “sex and gender” writers aren’t like this. At least not publicly. They only write about one subject. Their entire careers are only about writing on one thing: how bad men are.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m definitely not opposed to ideological writing. And I’m certainly not arguing that writers who think differently from me shouldn’t be “allowed” to write. But what I’m trying to point out is a social situation wherein public writers who only write about how literally one half of all human beings are garbage—and who tie every unrelated news item into that narrative—are able to make a living doing so in mainstream publications, because an environment has been fostered where doing such is not only acceptable, but commendable and “brave” (oh how they love to call each other “brave”!) If you want to trash men, even under the guise of wanting to “improve” them, you can get published in The New Yorker. If you want to trash men, you can get published in Vanity Fair or Harpers Bazaar. If you want to trash men, Huffington Post is yours. So is the Washington Post. So is Refinery 29. So is Buzzfeed. And hell, Vox was practically made for you. Even men’s magazines like GQ and Esquire are now onboard. But if you write anything that challenges the idea of “toxic masculinity” or “male privilege”, or even write a piece that says most men as individuals are not sexist or harassers, good luck finding any mainstream publication willing to print it. Not bad for a society that is still, allegedly, a patriarchy!

Of course, I can’t help but guess what the reaction would be if the genders were reversed just once. I think most of us know that if a male writer attempted to pontificate about the nature, psychology, and expressions of femininity, he would be laughed at, vilified, and would never check his email again for the rest of his life. And could you even imagine what would happen to that guy if he assured readers he didn’t hate women, he was just trying to “improve” them? It’d be dangerous even to attend his funeral. But female writers regularly pontificate about the nature, psychology, and expressions of a masculinity they have no personal experience of. And we applaud them for it. They’re so brave.

Concluding Thoughts

1. Reading over this piece before I hit “Publish”, my first thought is a cynical prediction of some truly ridiculous responses. Among which, that I wish to “put women back in their place”, or that I’m trying to “legitimize misogyny”, or that this is just 11,000 words of “male tears”. It’s very likely that I’ll be told that any criticism against any form of feminism contributes to an unsafe world for women, as well as condescendingly be reminded that “words have power”. Of course, I fear an accusation of a more serious nature as well; that because I’ve criticized MeToo and have been skeptical about the 2% false rape statistic, this must mean I don’t care about victims of sexual harassment, sexual assault, or rape. While I could swear to you up-and-down that this isn’t true—and that, like any decent human being, I do care—I’m also convinced that no amount of reassurance I give will stop readers who hate this article from hurling the charge regardless.

2. My second thought is a more personal one, though I think a lot of men have this same thought, and that is how exactly we respond to the feminist label. The word “feminism” is like the word “patriot”, in that its dictionary definition has almost become irrelevant in the face of the behavior of its loudest proponents.

The definition of a patriot, for example, is “one who loves and supports his or her country”, which definitely describes how I feel. But when we hear the word “patriot” in 2019, we don’t think “love and support for country” anymore. We think militias. We think “rightwing”. We think about crazy Ted Nugent. If you were a 90s kid, you probably think Timothy McVeigh. So now, because of how the word has been tainted, I would rarely use “patriot” as a description for who I am, even though I’m still a very loyal American.

The definition of feminism, yes, is “advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes”. But so what? That’s not what people see. We don’t see “equality of the sexes”, we see your op-eds. We see Sarah Silverman’s “Sorry, it’s a boy.” We see Maureen Dowd tell us we’ve stopped evolving and that we should just do whatever she tells us to do. So stop explaining the definition of feminism to men when they express to you that they don’t identify as one. It’s not the point. Even though I believe in equality of the sexes, I’m reluctant to refer to myself as a “feminist” because—like “patriot”—most of the people who go around calling themselves that give the term a very bad reputation. It’s now a tainted word.

3. My third and final thought is directed at the male readers of this piece who are mainly dealing with the questions of 1) “How do we raise our boys?”, and 2) “What do we do, in general, about the problem of being hated in American pop culture and society?”

In regard to the first question, I’ll offer an answer, but a bashful one, because I’m not a dad. I’ve always wanted to be a dad, and someday I’m sure I will be, but I’m not one yet. So the answer I’m about to give, unfortunately, doesn’t have the benefit of direct experience. Nevertheless, I think men in the 21st century should read to their sons the old stories of knights and cowboys and pirates and soldiers. Give them heroes. I think men in the 21st century should wrestle with their sons. Buy them that BB gun when they hit second grade and take them hunting in third. Teach them not to be afraid to approach women. Tell them they are not the problem.

As far as the answer to the second question goes—about how best to handle being demonized because of your gender and the supposed “threat” you embody—the worst part is I really don’t have an answer to that one. I don’t know. The problem of how men are demonized is clear to diagnose, but Jesus Christ the solution beats the hell out of me.

But maybe for right now it’s enough to just name the problem. Maybe for right now it’s enough to say that the problem exists. Maybe just doing that will lay the groundwork for a solution down the road. But for now I have no idea what “men are supposed to do”. I do wish all men who are eager to become their best selves and find true love the best of luck though, hoping against hope that Douglas Murray is wrong when he writes—in The Spectator—that the consequence of this new sexual counter-revolution is going to be no sex at all.

Citations

Because most of the information in this article that would require citation is linked directly to their sources, the only information I couldn’t link, or chose not to link, is the following:

Steven Pinker’s quote in The Blank Slate—quoted in the portion on boyhood—can be found on page 340 (or 7637 of 13536 if you’re reading the Kindle edition).

You can find the stolen car analogy—referenced in the MeToo portion—in VICE, Mic, and in a statement given to WHYY by Carol Tracey, executive director of the Women’s Law Project.

The studies discovered and compiled by forensic criminologist Dr. Brent Turvey for his book False Allegations: Investigative & Forensic Issues In Fraudulent Reports Of Crime—which I mentioned in the MeToo portion—are as follows: Jordan, “Beyond Belief? Police, Rape, & Women’s Credibility”, Criminal Justice: International Journal of Policy & Practice, 2004 (false report rate at 41%); Lea, Lanvers, Shaw, “Attrition In Rape Cases”, British Journal of Criminology, 2003 (false report rate at 11%); Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate/Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary, “A Report On The Joint Inspection Into The Investigation & Prosecution Of Cases Involving Allegations Of Rape”, London Home Office, 2002 (false report rate at 11.8%); Kennedy & Witkowski, “False Allegations Of Rape Revisited: A Replication Of The Kanin Study”, Journal Of Security Administration, 2000 (false report rate at 32%); Kanin, “False Rape Allegation”, Archives Of Sexual Behavior, 1994 (false report rate at 41%); Brown, Crowley, Peck, Slaughter, “Patterns Of Genital Injury In Female Sexual Assault Victims”, American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1997 (false report rate at 13%); Greenfield, “An Analysis Of Data On Rape & Sexual Assault: Sexual Offenses & Offenders”, Department of Justice, 1997 (false report rate at 8-15%); MacDonald, “False Accusations Of Rape”, Medical Aspects Of Human Sexuality, 1973 (false report rate at 25%).